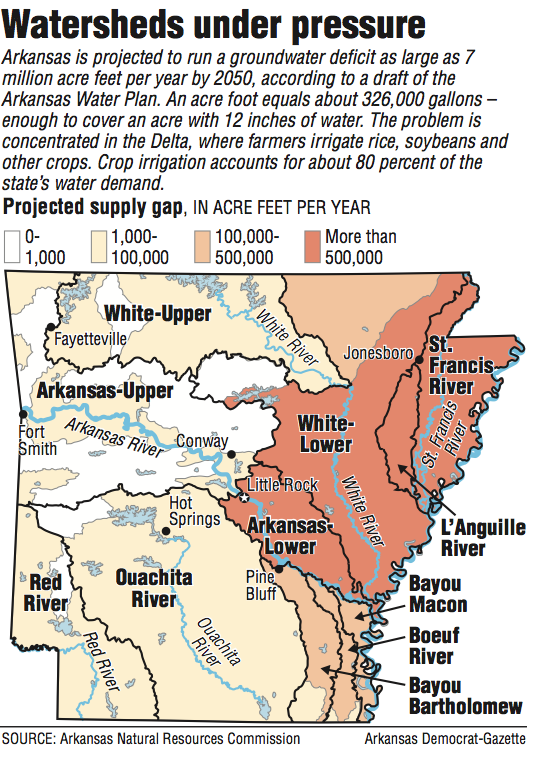

Delta groundwater lessens

In order to save their main water source, farmers in the Delta will need to find new sources of water and conserve what they have, according to the newly released Arkansas Water Plan draft.

For a century, Delta farmers have taken more water from the ground than nature puts back in. Extensive irrigation has allowed the region to thrive during dry seasons that decimate other states. But unless farmers find ways to reduce their reliance on groundwater, the resource will become more expensive and difficult to pump until it dries up.

"I would like to find the person that could tell us how to get the individual water user to see their self interest is tied up in the whole, but that's what's difficult," said Edward Swaim, water division manager for the Arkansas Natural Resources Commission. "And that's the hard part with groundwater in particular."

Swaim wants to avoid a situation in which farmers, acting individually for the good of their crops, continue to irrigate at the current rate with the same methods -- a response that's perhaps in the best interest of the individual farms in the short term, but not the group's long-term interest. It's a phenomenon known as a tragedy of the commons.

To avoid that outcome, Swaim said the last thing the state wants to do is control water use. Instead, he hopes the final Arkansas Water Plan spurs action through education, combined with tax credits and other incentives. The final plan is expected to be released in November.

"From everything I read, the last thing that works is to have the state come in and ration it," he said. "What good do you do if the state says you can't have a resource? That's the same as the resource going away."

Past warnings have not resulted in enough action to reverse the problem. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said groundwater was being tapped at a rate that exceeded its ability to recharge as far back as 1915. A state water resources report acknowledged the problem as early as 1939. And the state's last water plan -- published in 1990 -- recommended keeping a set "safe level" of water and reducing pumping by about 20 percent to sustain it, but no restrictions were ever placed on water.

Recently, water withdrawals have been double nature's deposits. And according to the plan, the groundwater deficit could be as large as 2.3 trillion gallons per year by 2050 -- the equivalent of about 3.5 million Olympic-size swimming pools.

The state has enough excess surface water to make up for the shrinking supply of groundwater -- around 2.8 trillion gallons per day -- but that water doesn't necessarily flow in the right areas or at the right times. It would have to be diverted and stored to be used, an expensive proposition.

Chris Henry, an assistant professor of Extension biological and agricultural engineering at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, said developing a multi-pronged approach to water use is key.

"If you make some conservation changes and develop water resources, by doing those two things, you could become sustainable," he said. "How you do that is the question, because you have to keep a level playing field."

Two ongoing projects are developing more water sources for farmers.

The Grand Prairie Area Demonstration Project will build new reservoirs between the White and Arkansas rivers on about 8,800 acres of farmland, doubling the current amount of usable, above-ground water storage. The project is about a quarter complete.

The Bayou Meto Water Management Project will divert Arkansas River water to convert a quarter million acres of farmland from groundwater to surface water irrigation. The project is about 13 percent complete.

Together, the projects will cost more than $1 billion and affect farms in Arkansas, Lonoke, Monroe, Prairie and Jefferson counties.

Despite their scale, these projects won't be enough to close the groundwater deficit.

Henry said if the state steps in, it matters how it does so. In an allocation system, farmers tend to use all the water they're allowed -- whether it's needed or not. He praised Nebraska's system, where natural resource districts are governed by farmers who have the ability to limit water use.

"When you let farmers govern themselves, they like the local control far better," he said.

Swaim also stressed that if control becomes necessary, he wants it to be local, and the draft report looked to Union County as an example of how that could be done.

In 1999, the United States Geological Survey created a model that showed that unless the county reduced its groundwater consumption by 72 percent in five years, the county would lose its supply.

Sherrel Johnson, who was president of the Union County Chamber of Commerce at the time, helped assemble stakeholders. The group went to the Arkansas Legislature to get permission to set up a county water board -- the first and so far only such board in Arkansas, although the legislation allows similar boards to be set up in any county with a critical groundwater supply.

"I think the process that we used to secure funding and build consensus is a good model to follow," she said. "No other organization had the legal authority to do what Union County wanted to do."

The board built the Ouachita River Alternative Water Supply Project. It takes surface water from the river and feeds it to several major industries in the county, letting the groundwater supply recover.

"This may be the country's only project in which residents wrote the law that created the state's first critical county conservation board, allowed themselves to be taxed once, then voted an additional temporary sales tax on themselves," the draft report states.

Since October 2004, groundwater levels have risen from 10 feet to almost 70 feet as a result of the Ouachita River Alternative Water Supply Project.

"That project just seems unbelievable," Swaim said. "I think this model should be used all over the country for how to get stuff done."

There are major differences between farming in the Delta and heavy industry in Union County. Instead of a handful of companies draining a relatively small underground water source, thousands of farmers are draining an expansive water source.

And unlike Union County, in many areas there is no surface water source that farmers could utilize. Those farmers are relying on those with access to surface water to switch so they can continue to use groundwater.

Johnson, who has one of the project's major facilities named after her, said whatever the process, the key is to bring everyone to the table.

"What we offer is the process itself, not necessarily the method," she said.