Big firms' efforts lift up region

Rural areas rarely become economic powerhouses, but Northwest Arkansas is an exception. In the past few decades, it has become the state’s fastest-growing region because some large companies there banded together to advance a common set of goals.

Economic incentives from the Arkansas Economic Development Commission played little to no role in the efforts to build a better highway there and a larger airport, improve the area’s water systems and create cultural attractions that allowed the companies to grow and the broader economy to flourish.

Instead, the largest companies in the region — Wal-Mart, Tyson Foods and J.B. Hunt — created the Northwest Arkansas Council around 1990 to advocate at the state and federal level for the things they needed.

Sam Walton, Don Tyson and Johnnie Bryan Hunt created the council because an inadequate transportation system limited their companies’ future growth, said Uvalde Lindsey, the council’s first executive director.

“We needed to all pick up the same hymnal, turn to the same song and get on the same verse and sing together, because together, we were a much louder and much more effective chorus in telling our story,” Lindsey said.

Lindsey is now a Democratic state senator who represents Fayetteville.

Back in the 1990s, Northwest Arkansas was among the most populous parts of the country that still lacked direct access to an interstate highway and to a large airport.

“You can’t grow community, you can’t attract population, you can’t do any of those things necessary unless you have the necessary physical infrastructure to move people and goods in a convenient fashion,” Lindsey said.

So Lindsey, while director of the Northwest Arkansas Economic Development District, spearheaded an effort to transform a mishmash of roads in multiple states into a cohesive U.S. 412. In the wake of that success, he was hired by Walton, Tyson and Hunt to find a way to build the region an interstate-quality highway and create a larger airport.

Interstate 49 and the Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport in Highfill were big factors in transforming the region. They cost about $500 million and $110 million, respectively, to build, Lindsey said.

The federal government paid for half of the interstate and 90 percent of the airport, he said.

“It’s like baking a cake. You throw all of that into a mix, and you’ll get a cake. Is the cake good or not? Depends on the quality of the ingredients,” Lindsey said.

“People come, jobs are created where folks can make a profit, where they can make money. You’ve got to have infrastructure to do that. You’ve got to have land, qualified people, good utilities, a positive cost structure, good utility rates.”

Lindsey said economic development incentives — tax credits, grants and other programs like those from the state economic development agency — are icing on the cake.

“You don’t get to the icing without the ingredients,” he said.

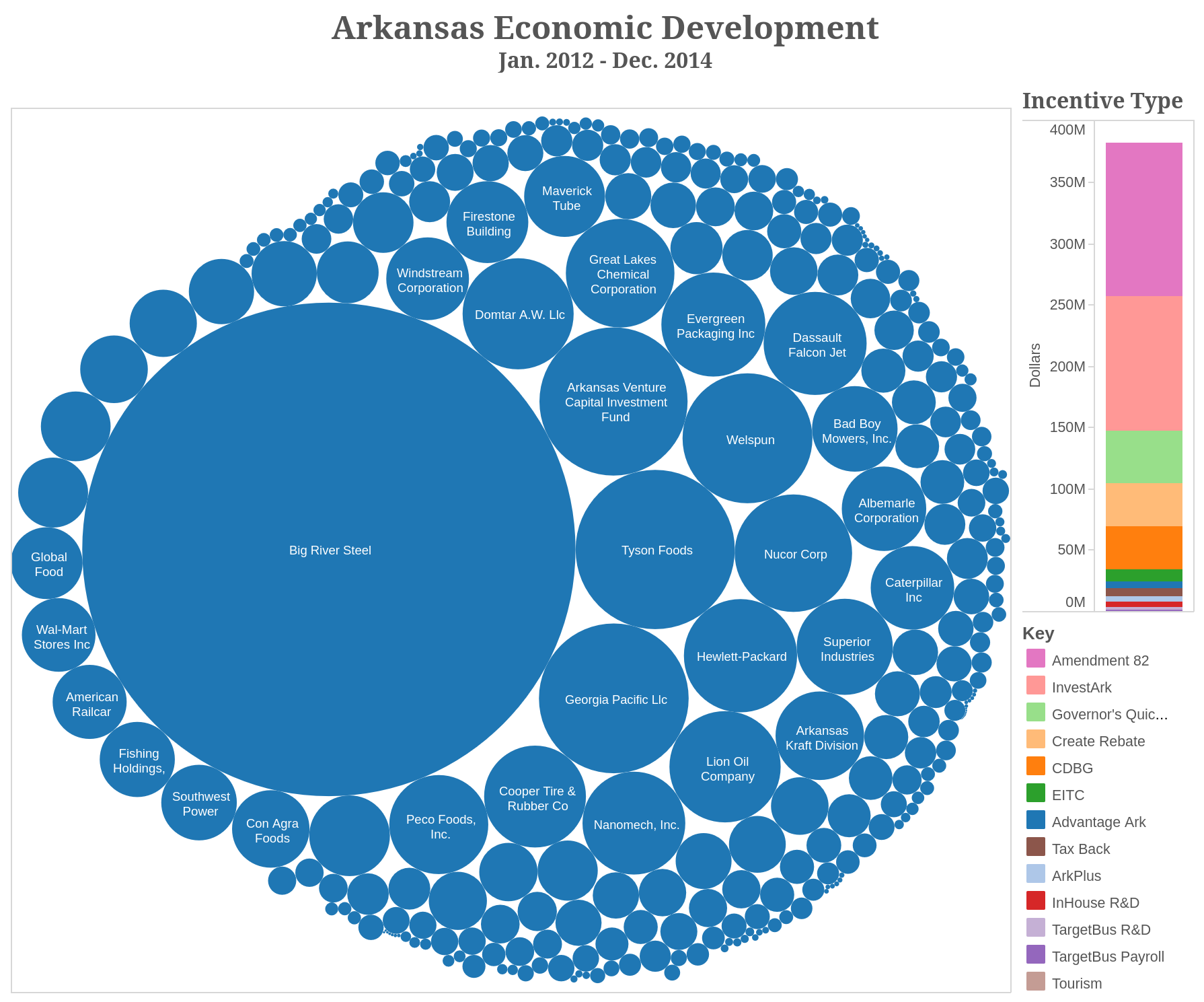

[Explore economic development incentive data in this interactive graphic]

The impact on the one-time mostly rural northwest part of the state has been phenomenal.

“You can’t imagine the change from the ’50s or ’60s — from the time period when the area was so very rural,” said Kathy Deck, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville.

“I think it provides a great story of hope when we talk about the rest of the state.”

From 2000 to 2010, the U.S. Census recorded a 44 percent increase in population in Benton County alone. And in November, Washington and Benton counties ranked first and second for the lowest unemployment rates in Arkansas.

Northwest Arkansas’ major companies don’t put their highest priority on reducing their tax loads through state incentives. The companies are more concerned about attracting younger talent, said Mike Malone, chief executive of the Northwest Arkansas Council.

“We don’t hear much else when we talk to these companies,” he said. “Quite frankly, we compete very well for the midcareer professional. We attract those people in droves. It’s the next generation we’re concerned about right now.”

National surveys show that Arkansas is among the least-expensive places to do business. In 2015, Forbes ranked Arkansas No. 3 in business cost — but No. 38 in quality of life and No. 44 in labor supply.

Northwest Arkansas companies — and their affiliated families — have spent hundreds of millions in the region to improve the quality of life.

Alice Walton invested more than $1 billion in Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, a world-class museum in Bentonville that has stimulated tourist interest in the area.

The Walton Family Foundation said it invested $27 million in Northwest Arkansas projects in 2014, including $5.4 million in the new Amazeum and hundreds of thousands of dollars in the area’s burgeoning bicycling and walking trail system.

There’s also the Walmart Arkansas Music Pavilion in Rogers that hosts big-name concerts, the Walton School of Business at the University of Arkansas and the Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville.

Wal-Mart received $2.8 million in Arkansas Economic Development Commission payments from 2012-14.

“We want to do our part to make Northwest Arkansas a great place for our associates to live and to help us attract top global talent,” Betsy Harden, a Wal-Mart spokesman, said in an email. “Our investment — which is both financial and human capital — is an investment that pays returns through creating a high quality of life for associates and the broader population and a strong climate for business success.”

Tyson Foods announced in October that it planned to add on to its former headquarters in downtown Springdale to create a two-story corporate office building for about 250 employees.

The company also has donated $1 million to the Downtown Springdale Alliance, which is working to revitalize Springdale’s downtown, and said it would renovate its building at 516 E. Emma Ave., which will become Tyson Foods’ Northwest Arkansas employment center and company store.

And in March, a $5 million gift from Tyson Foods and the Tyson family helped create a new agricultural research center for the University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture. The John W. Tyson building already houses the UA poultry science department.

Tyson was the No. 2 recipient of Arkansas Economic Development Commission grants from 2012-14. The state awarded about $13 million to the company, which had sales of more than $40 billion in fiscal 2015 and posted a $568 million profit.

“Like other Arkansas businesses that invest in the state and provide jobs, we apply for and use tax credits to help offset the cost of these capital expenditures so we can continue to be competitive while doing business here,” said Worth Sparkman, a spokesman for the company.

“We’re glad to be headquartered in Springdale and plan to invest in this city and the state for years to come.”

Sparkman said the company spent more than $400 million in Arkansas plant locations between 2012 and 2014, but applied for state economic development tax credits for “a fraction of the total projects.” The money went to modernize plants, ensure food safety, protect workers and make more products, he said.

Sparkman noted that some of the state payments involved the company’s Discovery Center in Springdale, which opened in 2006. The 100,000-square-foot pilot plant produces and evaluates potential new products and packaging.

The J.B. Hunt family gave $5 million in November to help build a Springdale nature center. Jones Center officials also announced a gift in February from Johnelle Hunt, widow of the company’s founder, although the amount was not disclosed.

The company received $185,000 in Arkansas Economic Development Commission payments from 2012-14. A spokesman declined to comment for this article.

Trails, parks and entertainment have become important to attracting millennials, officials say.

“These things — these amenities that we talk about — 10 years ago, in economic development circles, they would have been kind of squishy,” said Michael Harvey, chief operating officer for the Northwest Arkansas Council. “Craft brewers and local food and trails — that is economic development strategy 101 now.”

The companies have done a lot for the region, but he’s not sure he wants Northwest Arkansas to be labeled as a company town.

“There’s two sides of the coin on that. If you’re perceived as a company town, it can be a detriment to people actually looking here who have never been here,” he said. “On the other hand, [the companies] are tremendous assets. They’ve caused so much growth.”

Outside of expanding the area’s amenities, Harvey said, there’s a mismatch between what employers need in a workforce and the educations that high school and college students receive. More technical education would benefit the economy and students, he said.

Could the state do without economic development grants?

Harvey said that would depend on what other states did.

“I think that if everyone else disarmed, I’d say 100 percent, absolutely. The resources that we’re all spending on incentives need to be plowed back into workforce programs. But if no one else has disarmed, it gets to be a real challenge. It really does,” he said.

“I’d love to see it tried. I just don’t think if I would be willing to say, if I were governor, let’s just stop doing incentives.”